80 years of silence: Their great-uncle was in a concentration camp

The Genenger siblings found out that their great-uncle Robert had been imprisoned in a concentration camp through an appeal for information that appeared in a local newspaper. The Nazis persecuted the trained roofer as a “career criminal.” They confiscated his personal belongings, which we have now returned to his relatives.

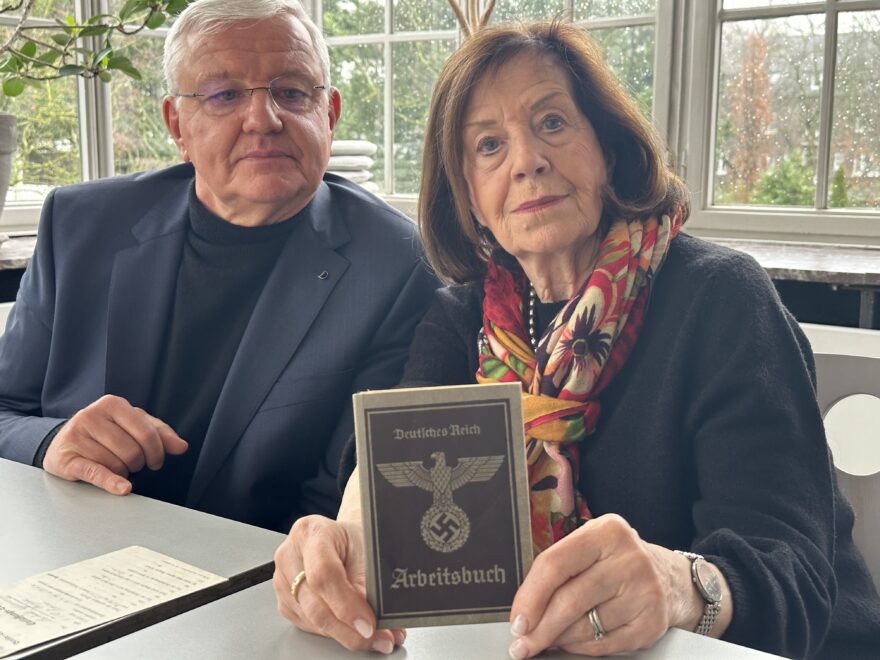

“We really didn’t know anything at all about Robert Genenger. The family never spoke of him,” explained August Genenger, his great-nephew. On February 26, the Arolsen Archives returned his great-uncle’s personal documents to him and his sister, Martha Stang. Now they want to pass on Robert Genenger’s story to the next generation of the family.

Imprisoned as a “career criminal”

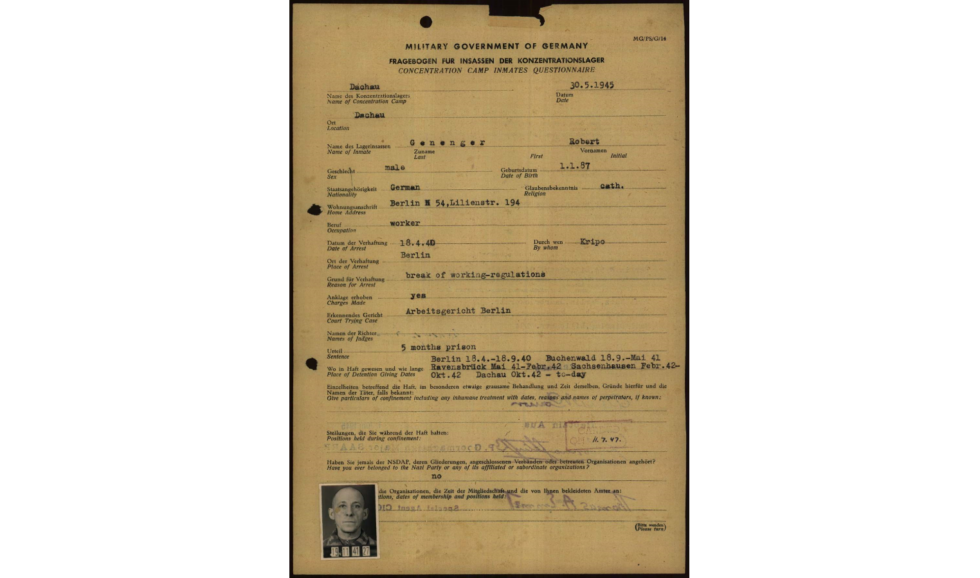

Robert Genenger was born on January 1, 1887, in Krefeld. His father Friedrich owned a roofing company that still exists in Krefeld today. Robert completed his apprenticeship in the family business in 1904. Little is known about his subsequent career or about his life in general. According to information contained in the documents, he worked in various companies in Berlin from 1938 onwards and was probably divorced. The criminal investigations police arrested the roofer on April 19, 1941, for allegedly “refusing to work.” In September 1941, after five months in prison in Berlin-Spandau, he was taken into “protective custody” – without a trial and for an indefinite period.

The SS deported Robert to Buchenwald concentration camp on November 18, 1941, where he was categorized as a “career criminal” and assigned to a penal company. In March 1942, the Nazis transported him first to Ravensbrück concentration camp and then to Sachsenhausen. In mid-November 1942, he was transferred to Dachau. Robert Genenger survived several years of inhumane imprisonment, and in May 1945, he told the Allies that he wished to return to Berlin.

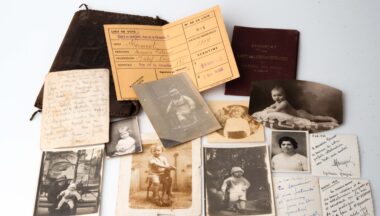

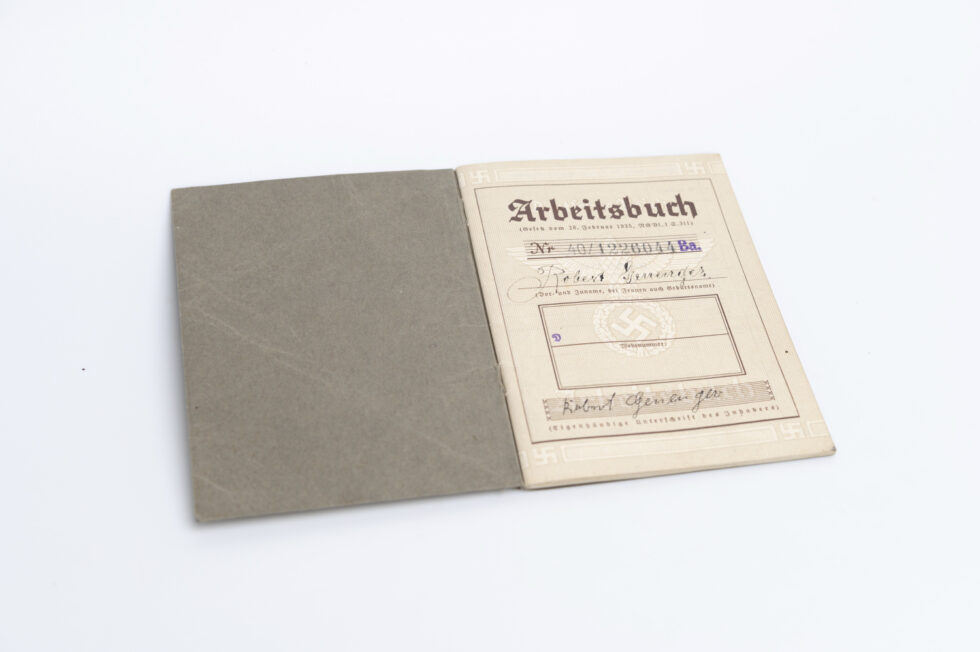

In 1964, the International Tracing Service (now the Arolsen Archives) tried in vain to find Robert Genenger’s address in Berlin because they wanted to return the personal belongings that were taken away from him during his incarceration: a certificate of release from the Berlin-Spandau prison and his work book. Starting in the mid-1930s, all German workers had to hand in a work book to their employers – later, this applied to all civilian forced laborers from the occupied territories, too. These work books were used to manage and coordinate so-called labor assignments; they restricted people’s freedom to exercise a trade or profession. Would Robert Genenger have even wanted these documents to be returned to him? After all, they would probably have brought back bad memories.

Items returned to his family in Krefeld

When the #StolenMemory traveling exhibition was visiting Krefeld last fall, we took the opportunity to draw attention to Robert Genenger’s story. His personal belongings were the only ones in the Arolsen Archives collection that had any connection to the city of Krefeld.

Fabian Schmitz works at the Villa Merländer memorial, the organization that hosted the exhibition. He used the city archives to search for the family, and the Rheinische Post newspaper published an appeal for information. August Genenger responded to the appeal when a customer of the roofing company founded in 1887 that he ran up until 11 years ago drew his attention to the newspaper article.

August Genenger is Robert Genenger’s great-nephew. His family never spoke of Robert, let alone of his imprisonment in the camp. Suffering persecution, especially as a “career criminal,” was something people were embarrassed about, even when Nazi rule came to an end. That explains why many families kept these stories quiet or tried to forget them all together. At the ceremony held to mark the return of his great-uncle’s personal effects, August Genenger mentioned that the family had been quite pro-Nazi: “I can remember situations where people would say things like ‘That would never have happened under Adolf.’”